Author

Author

|

Topic: Anyone up for a little Time Travel? (Read 1085 times) |

|

Bass

Initiate

Posts: 196

Reputation: 5.19

Rate Bass

I'm a llama!

|

|

Anyone up for a little Time Travel?

« on: 2007-07-04 12:10:05 » |

|

Hypothetical question here.

Let's say a time machine has been invented. If you (a virian, full of memes just waiting to infect the world) could go back in time, and could take one thing with you, what would it be? It could be an object, an idea, anything.

My next question would be what time period would you travel back to and what would you do?

|

|

|

|

|

Blunderov

Adept

Gender:

Posts: 3160

Reputation: 7.99

Rate Blunderov

"We think in generalities, we live in details"

|

|

Re:Anyone up for a little Time Travel?

« Reply #1 on: 2007-07-04 17:45:27 » |

|

[Blunderov] A time machine would not be able to go back to a time before the time machine itself had been invented. So the time machine would have to come from a non-human source, perhaps somewhere in Peru.

Given the chance I would love to see the Jurassic. Might need a rather special vehicle though. An Abrahams tank might be just the thing.

|

|

|

|

|

Hermit

Adept

Posts: 4289

Reputation: 7.80

Rate Hermit

Prime example of a practically perfect person

|

|

Re:Anyone up for a little Time Travel?

« Reply #2 on: 2007-07-06 07:12:36 » |

|

Blunderov, speaking hypothetically, if a "space-time machine" can exist (and it is important to recognize its full name), then it can exist. It's a pure tautological issue. The corollary is that if one can't exist, it won't exist, and the hypothec will fail. There are no paradoxes, just limited perceptions.

I have suggested a number of possible answers to Bass' interesting question based on the interjection of the least possible technology at a critical juncture. It is important to recognise how very interdependent the various technologies we have are, and this is what drove my choice of technology. The times and locations were chosen based on recognizing critical junctures and times when a beneficial movement failed for identifiable reasons, and where a small change not far from available technology and capability could perhaps have prevented the abortion of something good and thus have made a dramatic difference to the future and our present. In approximate chronological order, I might:

Take the technology to produce wind turbines back to pre-Vesuvian Republican Rome and introduce it via Pliny to the civil engineers building the aqueducts, who definitely had the need and capacity to appreciate it properly. That one addition to Roman technology, with implications for water movement, marine and land transport, grain processing and many quality of life issues would likely have meant that the impact of the droughts in Egypt would have been much less, slavery would have been made uneconomical, and probably ensured the advent of an energy rich modernity at a time when populations were yet of manageable size and while not introducing fossil fuel pollution issues. So I think that the Republic would likely have survived and lead to an early modern age, while the Empire, and later the Christians, would not have had the chance to take over and destroy, for 1500 or so years, what civilization we had painfully established.

Provide the Librarians of Alexandria with the ability to print and distribute cheaply the contents of their archives, limiting the ability of the Christians to suppress our - and more importantly their - origins and almost incidentally most of the accumulated wisdom of 3,500 years. Had this happened early enough, this one action might well have prevented the dominance of Europe by of Christianity, even the birth of Islam, and would likely have resulted in the much wider distribution of non-aggressive neoplatonic concepts and an ideal towards a global Athenian utopia.

Provide the Moors with gunpowder and cannon technology in the early 12th Century. Their intellectual, chemical and metalworking capacities would have been adequate to implement an armament industry; which would have prevented their defeats at the hands of the Franks, stopped the crusades from ever happening, and ensured that medical knowledge was available to Europe when the plagues struck. This would also probably have prevented the transition to the delusions of "States" as entities - along with monetary economies based on the supposed value of scarcity; and lead to some form of viable socialism in the 14th Century.

Provide the Cathars with the elements of bio-warfare, probably based on anthrax and antibiotics, which would have allowed them to withstand the forces of France, Germany's Feudal Princes and the Papacy. This would likely have lead to an egalitarian, pastoral, neosocialist pan European commune; which would have avoided most of the self-inflicted European horrors between 1200 and 1950 - and also have likely prevented colonialism and the formation of the USA and Canada.

Provide Richard III with anti-personal mortars and guns with a reasonably high cyclic rate of fire akin to the muskets of the 1600s. This would have allowed him to defeat the combined forces of the French and Lancastrians, and would have resulted in introducing democratic ideas into England 200 years earlier than they were - and without the horrors of centuries of Catholic and Protestant infighting caused by Henry VIII's marital difficulties. This would likely have lead to England being much wealthier, leading the Humanitarian Renaissance in the 1500 or early 1600s and again, the probable instantiation of a European industrialized state without all the nastiness of the interminable French, Spanish and English wars, or evils of colonization.

Provided Leonardo da Vinci the secrets of the Bessemer process, which would have given him the material technology required to implement many of his more brilliant concepts. This would have almost certainly resulted in the eventual domination by the merchant motivated City States over the aristocracy and Papacy, limited the church and aristoct's ability to wage war, and in turn hastened the introduction of the modern industrial age, with all its commensurate benefits, by some 400 years.

Provided the Amerinds with bio-warfare components including smallpox and inoculation technology. This would have prevented the early depopulation of what is today the US and Canada, and provided effective means of preventing additional encroachment into the area by the nasty grave robbing, plundering religious fanatics who went to the USA to establish their own nasty religious tyrannies (rather than to escape the tyranny of others). In turn, this would have prevented the globalization of the first and second world wars, and possibly much of the nastiness of communism.

There are of course a near infinity of other possibilities. These were merely first to mind.

Regards

Hermit

|

With or without religion, you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion. - Steven Weinberg, 1999

|

|

|

Blunderov

Adept

Gender:

Posts: 3160

Reputation: 7.99

Rate Blunderov

"We think in generalities, we live in details"

|

|

Re:Anyone up for a little Time Travel?

« Reply #3 on: 2007-07-06 16:02:25 » |

|

[Blunderov] Hello Hermit. I've changed my mind a lot about time travel. Used to be that it was self evident to me that the whole idea is ridiculous. Now I'm not so sure.

According to David Deutsch inter-universe travel closely resembling time-travel might well be possible.

This is chapter 12 from his book "The Fabric of Reality".

I know it's quite long. Hopefully it is worthwhile.

Best Regards.

The Fabric of Reality

Chapter 12

Time Travel

It is a natural thought, given the idea that time is in some ways like an additional, fourth dimension of space, that if it is possible to travel from one place to another, perhaps it is also possible to travel from one time to another. We saw in the previous chapter that the idea of 'moving' through time, in the sense in which we move through space, does not make sense. Nevertheless, it seems clear what one would mean by travelling to the twenty-fifth century or to the age of the dinosaurs. In science fiction, time machines are usually envisaged as exotic vehicles. One sets the controls to the date and time of one's chosen destination, waits while the vehicle travels to that date and time (sometimes one can choose the place as well), and there one is. If one has chosen the distant future, one converses with conscious robots and marvels at inter¬stellar spacecraft, or (depending on the political persuasion of the author) one wanders among charred, radioactive ruins. If one has chosen the distant past, one fights off an attack by a Tyrannosaurus rex while pterodactyls flutter overhead.

The presence of dinosaurs would be impressive evidence that we really had reached an earlier era. We should be able to cross-check this evidence, and determine the date more precisely, by observing some natural long-term 'calendar' such as the shapes of the constellations in the night sky or the relative proportions of various radio¬active elements in rocks. Physics provides many such calendars, and the laws of physics cause them to agree with one another when suitably calibrated. According to the approximation that the multiverse consists of a set of parallel spacetimes, each consisting of a stack of 'snapshots’ of space, the date defined in this way is a property of an entire snapshot, and any two snapshots are separ¬ated by a time interval which is the difference between their dates. Time travel is any process that causes a disparity between, on the one hand, this interval between two snapshots, and on the other, our own experience of how much time has elapsed between our being in those two snapshots. We might refer to a clock that we carry with us, or we might estimate how much thinking we have had the opportunity to do, or we might measure by physiological criteria how much our bodies have aged. If we observe that a long time has passed externally, while by all subjective measures we have experienced a much shorter time, then we have travelled into the future. If, on the other hand, we observe the external clocks and calendars indicating a particular time, and later (subjectively) we observe them consistently indicating an earlier time, then we have travelled into the past.

Most authors of science fiction realize that future- and past-¬directed time travel are radically different sorts of process. I shall not give future-directed time travel much attention here, because it is by far the less problematic proposition. Even in everyday life, for example when we sleep and wake up, our subjectively experienced time can be shorter than the external elapsed time. People who recover from comas lasting several years could be said to have travelled that many years into the future, were it not for the fact that their bodies have aged according to external time rather than the time they experienced subjectively. So, in principle, a technique similar to that which we envisaged in Chapter 5 for slowing down a virtual-reality user's brain could be applied to the whole body, and thus could be used for fully fledged future-directed time travel. A less intrusive method is provided by Einstein's special theory of relativity, which says that in general an observer who accelerates or decelerates experiences less time than an observer who is at rest or in uniform motion. For example, an astronaut who went on a round-trip involving acceleration to speeds close to that of light would experience much less time than an observer who remained on Earth. This effect is known as time dilation. By

accelerating enough, one can make the duration of the flight from the astronaut's point of view as short as one likes, and the duration as measured on Earth as long as one likes. Thus one could travel as far into the future as one likes in a given, subjectively short time. But such a trip to the future is irreversible. The return journey would require past-directed time travel, and no amount of time dilation can allow a spaceship to return from a flight before it took off.

Virtual reality and time travel have this, at least, in common: they both systematically alter the usual relationship between exter¬nal reality and the user's experience of it. So one might ask this question: if a universal virtual-reality generator could so easily be programmed to effect future-directed time travel, is there a way of using it for past-directed time travel? For instance, if slowing us down would send us into the future, would speeding us up send us into the past? No; the outside world would merely seem to slow down. Even at the unattainable limit where the brain operated infinitely fast, the outside world would appear frozen at a particular moment. That would still be time travel, by the above definition, but it would not be past-directed. One might call it 'present¬directed' time travel. I remember wishing for a machine capable of present-directed time travel when doing last-minute revision for exams - what student has not?

Before I discuss past-directed time travel itself, what about the rendering of past-directed time travel? To what extent could a virtual-reality generator be programmed to give the user the experi¬ence of past-directed time travel? We shall see that the answer to this question, like all questions about the scope of virtual reality, tells us about physical reality as well.

The distinctive aspects of experiencing a past environment are, by definition, experiences of certain physical objects or processes - 'clocks' and 'calendars' - in states that occurred only at past times (that is, in past snapshots). A virtual-reality generator could, of course, render those objects in those states. For instance, it could give one the experience of living in the age of the dinosaurs, or in the trenches of the First World War, and it could make the constellations, dates on newspapers or whatever, appear correctly for those times. How correctly? Is there any fundamental limit on how accurately any given era could be rendered? The Turing principle says that a universal virtual-reality generator can be built, and could be programmed to render any physically possible environment, so clearly it could be programmed to render any environment that did once exist physically.

To render a time machine that had a certain repertoire of past destinations (and therefore also to render the destinations them¬selves), the program would have to include historical records of the environments at those destinations. In fact, it would need more than mere records, because the experience of time travel would involve more than merely seeing past events unfolding around one. Playing recordings of the past to the user would be mere image generation, not virtual reality. Since a real time traveller would participate in events and act back upon the past environment, an accurate virtual-reality rendering of a time machine, as of any environment, must be interactive. The program would have to calculate, for each action of the user, how the historical environment would have responded to that action. For example, to convince Dr Johnson that a purported time machine really had taken him to ancient Rome, we should have to allow him to do more than just watch passively and invisibly as Julius Caesar walked by. He would want to test the authenticity of his experiences by kicking the local rocks. He might kick Caesar - or at least, address him in Latin and expect him to reply in kind. What it means for a virtual-reality rendering of a time machine to be accurate is that the rendering should respond to such interactive tests in the same way as would the real time machine, and as would the real past environments to which it travelled. That should include, in this case, displaying a correctly behaving, Latin-speaking rendering of Julius Caesar.

Since Julius Caesar and ancient Rome were physical objects, they could, in principle, be rendered with arbitrary accuracy. The task differs only in degree from that of rendering the Centre Court at Wimbledon, including the spectators. Of course, the complexity of the requisite programs would be tremendous. More complex still, or perhaps even impossible in principle, would be the task of gathering the information required to write the programs to render specific human beings. But writing the programs is not the issue here. I am not asking whether we can find out enough about a past environ¬ment (or, indeed, about a present or future environment) to write a program that would render that environment specifically. I am asking whether the set of all possible programs for virtual-reality generators does or does not include one that gives a virtual-reality rendering of past-directed time travel and, if so, how accurate that rendering can be. If there were no programs rendering time travel, then the Turing principle would imply that time travel was physically impossible (because it says that everything that is physi¬cally possible can be rendered by some program). And on the face of it, there is indeed a problem here. Even though there are pro¬grams which accurately render past environments, there appear to be fundamental obstacles to using them to render time travel. These are the same obstacles that appear to prevent time travel itself, namely the so-called 'paradoxes' of time travel.

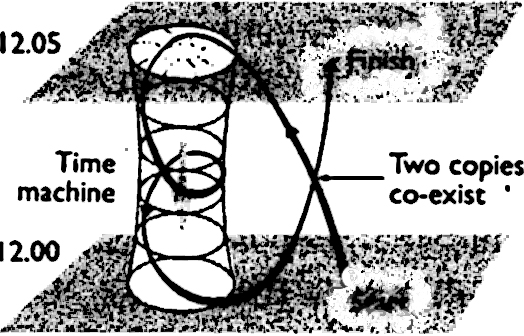

Figure 12.1 Spacetime path taken by time traveller Figure 12.1 Spacetime path taken by time traveller

Here is a typical such paradox. I build a time machine and use it to travel back into the past. There I prevent my former self from building the time machine. But if the time machine is not built, I shall not be able to use it to travel into the past, nor therefore to prevent the time machine from being built. So do I make this trip or not? If I do, then I deprive myself of the time machine and therefore do not make the trip. If I do not make the trip, then I allow myself to build the time machine and so do make the trip. This is sometimes called the 'grandfather paradox', and stated in terms of using time travel to kill one's grandfather before he had any children. (And then, if he had no children, he could not have had any grandchildren, so who killed him?) These two forms of the paradox are the ones most commonly cited, and happen to require an element of violent conflict between the time traveller and people in the past, so one finds oneself wondering who will win. Perhaps the time traveller will be defeated, and the paradox avoided. But violence is not an essential part of the problem here. If I had a time machine, I could decide as follows: that if, today, my future self visits me, having set out from tomorrow, then tomorrow I shall not use my time machine; and that if I receive no such visitor today, then tomorrow I shall use the time machine to travel back to today and visit myself. It seems to follow from this decision that if I use the time machine then I shall not use it, and if I do not use it then I shall use it: a contradiction.

A contradiction indicates a faulty assumption, so such paradoxes have traditionally been taken as proofs that time travel is imposs¬ible. Another assumption that is sometimes challenged is that of free will- whether time travellers can choose in the usual way how to behave. One then concludes that if time machines did exist, people's free will would be impaired. They would somehow be unable to form intentions of the type I have described; or else, when they travelled in time, they would somehow systematically forget the resolutions they made before setting out. But it turns out that the faulty assumption behind the paradoxes is neither the existence of a time machine nor the ability of people to choose their actions in the usual way. All that is at fault is the classical theory of time, which I have already shown, for quite independent reasons, to be untenable.

If time travel really were logically' impossible, a virtual-reality rendering of it would also be impossible. If it required a suspension of free will, then so would a virtual-reality rendering of it. The paradoxes of time travel can be expressed in virtual-reality terms as follows. The accuracy of a virtual-reality rendering is the faithfulness, as far as is perceptible, of the rendered environment to the intended one. In the case of time travel the intended environment is one that existed historically. But as soon as the rendered environ¬ment responds, as it is required to, to the user kicking it, it thereby becomes historically inaccurate because the real environment never did respond to the user: the user never did kick it. For example, the real Julius Caesar never met Dr Johnson. Consequently Dr Johnson, in the very act of testing the faithfulness of the rendering by conversing with Caesar, would destroy that faithfulness by creat¬ing a historically inaccurate Caesar. A rendering can behave accu¬rately by being a faithful image of history, or it can respond accurately, but not both. Thus it would appear that, in one way or the other, a virtual-reality rendering of time travel is intrinsically incapable of being accurate - which is another way of saying that time travel could not be rendered in virtual reality.

But is this effect really an impediment to the accurate rendering of time travel? Normally, mimicking an environment's actual behaviour is not the aim of virtual reality: what counts is that it should respond accurately. As soon as you begin to play tennis on the rendered Wimbledon Centre Court, you make it behave differently from the way the real one is behaving. But that does not make the rendering any less accurate. On the contrary, that is what is required for accuracy. Accuracy, in virtual reality, means the closeness of the rendered behaviour to that which the original environment would exhibit if the user were present in it. Only at the beginning of the rendering does the rendered environment's state have to be faithful to the original. Thereafter it is not its state but its responses to the user's actions that have to be faithful. Why is that 'paradoxical' for renderings of time travel but not for other renderings - for instance, for renderings of ordinary travel?

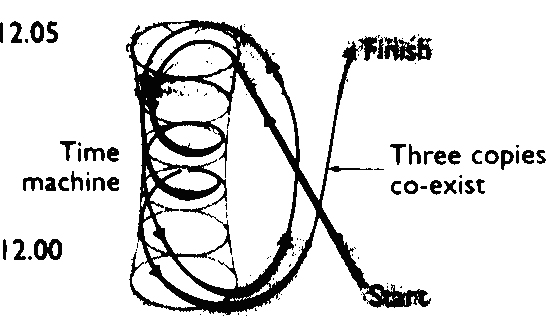

Figure 12.2 Repeatedly using the time machine allows multiple copies of the time traveller to co-exist. Figure 12.2 Repeatedly using the time machine allows multiple copies of the time traveller to co-exist.

It seems paradoxical because in renderings of past-directed time travel the user plays a unique double, or multiple, role. Because of the looping that is involved, where for instance one or more copies of the user may co-exist and interact, the virtual-reality generator is in effect required to render the user while simultaneously responding to the user's actions. For example, let us imagine that I am the user of a virtual-reality generator running a time-travel¬ rendering program. Suppose that when I switch on the program, the environment that I see around me is a futuristic laboratory. In the middle there is a revolving door, like those at the entrances of large buildings, except that this one is opaque and is almost entirely enclosed in an opaque cylinder. The only way in or out of the cylinder is a single entrance cut in its side. The door within revolves continuously. It seems at first sight that there is little one can do with this device except to enter it, go round one or more times with the revolving door, and come out again. But above the entrance is a sign: 'Pathway to the Past'. It is a time machine, a fictional, virtual-reality one. But if a real past-directed time machine existed it would, like this one, not be an exotic sort of vehicle but an exotic sort of place. Rather than drive or fly it to the past, one would take a certain path through it (perhaps using an ordinary space vehicle) and emerge at an earlier time.

On the wall of the simulated laboratory there is a clock, initially showing noon, and by the cylinder's entrance there are some instructions. By the time I have finished reading them it is five minutes past noon, both according to my own perception and according to the clock. The instructions say that if I enter the cylinder, go round once with the revolving door, and emerge, it will be five minutes earlier in the laboratory. I step into one of the compartments of the revolving door. As I walk round, my compartment closes behind me and then, moments later, reaches the entrance again. I step out. The laboratory looks much the same except - what? What exactly should I expect- to experience next, if this is to be an accurate rendering of past-directed time travel?

Let me backtrack a little first. Suppose that by the entrance there is a switch whose two positions are labelled 'interaction on' and 'interaction off'. Initially it is at 'interaction off'. This setting does not allow the user to participate in the past, but only to observe it. In other words, it does not provide a full virtual-reality rendering of the past environment, but only image generation.

With this simpler setting at least, there is no ambiguity or para¬dox about what images ought to be generated when I emerge from the revolving door. They are images of me, in the laboratory, doing what I did at noon. One reason why there is no ambiguity is that I can remember those events, so I can test the images of the past against my own recollection of what happened. By restricting our analysis to a small, closed environment over a short period, we have avoided the problem analogous to that of finding out what Julius Caesar was really like, which is a problem about the ultimate limits of archaeology rather than about the inherent problems of time travel. In our case, the virtual-reality generator can easily obtain the information it needs to generate the required images, by making a recording of everything I do. Not, that is, a recording of what I do in physical reality (which is simply to lie still inside the virtual-reality generator), but of what I do in the virtual environment of the laboratory. Thus, the moment I emerge from the time machine, the virtual-reality generator ceases to render the laboratory at five minutes past noon, and starts to play back its recording, starting with images of what happened at noon. It displays this recording to me with the perspective adjusted for my present position and where I am looking, and it continuously readjusts the perspective in the usual way as I move. Thus, I see the clock showing noon again. I also see my earlier self, standing in front of the time machine, reading the sign above the entrance and studying the instructions, exactly as I did five minutes ago. I see him, but he cannot see me. No matter what I do, he - or rather it, the moving image of me - does not react to my presence in any way. After a while, it walks towards the time machine.

If I happen to be blocking the entrance, my image will nevertheless make straight for it and walk in, exactly as I did, for if it did anything else it would be an inaccurate image. There are many ways in which an image generator can be programmed to handle a situation where an image of a solid object has to pass through the user's location. For instance, the image could pass straight through like a ghost, or it could push the user irresistibly away. The latter option gives a more accurate rendering because then the images are to some extent tactile as well as visual. There need be no danger of my getting hurt as my image knocks me aside, however abruptly, because of course I am not physically there. If there is not enough room for me to get out of the way, the virtual-reality generator could make me flow effortlessly through a narrow gap, or even teleport me past an obstacle.

It is not only the image of myself on which I can have no further effect. Because we have temporarily switched from virtual reality to image generation, I can no longer affect anything in the simulated environment. If there is a glass of water on a table I can no longer pick it up and drink it, as I could have before I passed through the revolving door to the simulated past. By requesting a simulation of non-interactive, past-directed time travel, which is effectively a playback of specific events five minutes ago, I necessarily relinquish control over my environment. I cede control, as it were, to my former self.

As my image enters the revolving door, the time according to the clock has once again reached five minutes past twelve, though it is ten minutes into the simulation according to my subjective perception. What happens next depends on what I do. If I just stay in the laboratory; the virtual-reality generator's next task must be to place me at events that occur after five minutes past twelve, laboratory time. It does not yet have any recordings of such events, nor do I have any memories of them. Relative to me, relative to the simulated laboratory and relative to physical reality those events have not yet happened, so the virtual-reality generator can resume its fully interactive rendering. The net effect is of my having spent five minutes in the past without being able to affect it, and then returning to the 'present' that I had left, that is, to the normal sequence of events which I can affect.

Alternatively, I can follow my image into the time machine, travel round the time machine with my image and emerge again into the laboratory's past. What happens then? Again, the clock says twelve noon. Now I can see two images of my former self. One of them is seeing the time machine for the first time, and notices neither me nor the other image. The second image appears to see the first but not me. I can see both of them. Only the first image appears to affect anything in the laboratory. This time, from the virtual-reality generator's point of view, nothing special has happened at the moment of time travel. It is still at the 'interaction off' setting, and is simply continuing to play back images of events five minutes earlier (from my subjective point of view), and these have now reached the moment when I began to see an image of myself.

After another five minutes have passed I can again choose whether to re-enter the time machine, this time in the company of two images of myself (Figure 12.2). If I repeat the process, then after every five subjective minutes an additional image of me will appear. Each image will appear to see all the ones that appeared earlier than itself (in my experience), but none of those that appeared later than itself.

If I continue the experience for as long as possible, the maximum number of copies of me that can co-exist will be limited only by the image generator's collision avoidance strategy. Let us assume that it tries to make it realistically difficult for me to squeeze myself into the revolving door with all my images. Then eventually I shall be forced to do something other than travel back to the past with them. I could wait a little, and take the compartment after theirs, in which case I should reach the laboratory a moment after they do. But that just postpones the problem of over¬crowding in the time machine. If I keep going round this loop, eventually all the 'slots' for time travelling into the period of five minutes after noon will be filled, forcing me to let myself reach a later time from which there will be no further means of returning to that period. This too is a property that time machines would have if they existed physically. Not only are they places, they are places with a finite capacity for supporting through traffic into the past.

Another consequence of the fact that time machines are not vehicles, but places or paths, is that one is not completely free to choose which time to use them to travel to. As this example shows, one can use a time machine only to travel to. times and places at which it has existed. In particular, one cannot use it to travel back to a time before its construction was completed.

The virtual-reality generator now has recordings of many different versions of what happened in that laboratory between noon and five minutes past. Which one depicts the real history? We ought not be too concerned if there is no answer to this question, for it asks what is real in a situation where we have artificially suppressed interactivity, making Dr Johnson's test inapplicable. One could argue that only the last version, the one depicting the most copies of me, is the real one, because the previous versions all in effect show history from the point of view of people who, by the artificial rule of non-interaction, were prevented from fully seeing what was happening. Alternatively, one could argue that the first version of events, the one with a single copy of me, is the only real one because it is the only one I experienced interactively. The whole point of non-interactivity is that we are temporarily preventing ourselves from changing the past, and since subsequent versions all differ from the first one, they do not depict the past. All they depict is someone viewing the past by courtesy of a universal image generator.

One could also argue that all the versions are equally real. After all, when it is all over I remember having experienced not just one history of the laboratory during that five-minute period, but several such histories. I experienced them successively, but from the labora¬tory's point of view they all happened during the same five-minute period. The full record of my experience requires many snapshots of the laboratory for each clock-defined instant, instead of the usual single snapshot per instant. In other words, this was a rendering of parallel universes. It turns out that this last interpretation is the closest to the truth, as we can see by trying the same experiment again, this time with interaction switched on.

The first thing I want to say about the interactive mode, in which I am free to affect the environment, is that one of the things I can choose to make happen is the exact sequence of events I have just described for the non-interactive mode. That is, I can go back and encounter one or more copies of myself, yet nevertheless (if I am a good enough actor) behave exactly as though I could not see some of them. Nevertheless, I must watch them carefully. If I want to recreate the sequence of events that occurred when I did this experiment with interaction switched off, I must remember what the copies of me do so that I can do it myself on subsequent visits to this time.

At the beginning of the session, when I first see the time machine, I immediately see it disgorging one or more copies of me. Why? Because with interaction switched on, when I come to use the time machine at five minutes past noon I shall have the right to affect the past to which I return, and that past is what is happening now, at noon. Thus my future self or selves are arriving to exercise their right to affect the laboratory at noon, and to affect me, and in particular to be seen by me.

The copies of me go about their business. Consider the compu¬tational task that the virtual-reality generator has to execute, in rendering these copies. There is now a new element that makes this overwhelmingly more difficult than it was in the non-interactive mode. How is the virtual-reality generator to find out what the copies of me are going to do? It does not yet have any recordings of that information, for in physical time the session has only just begun. Yet it must immediately present me with renderings of my future self.

So long as I am resolved to pretend that I cannot see these renderings, and then to mimic whatever I see them do, they are not going to be subjected to too stringent a test of accuracy. The virtual-reality generator need only make them do something - anything that I might do; or more precisely any behaviour that I am capable of mimicking. Given the technology that we are assuming the virtual-reality generator to be based on, that would presumably not be exceeding its capabilities. It has an accurate mathematical model of my body, and a degree of direct access to my brain. It can use these to calculate some behaviour which I could mimic, and then have its initial renderings of me carry out that behaviour.

So I begin the experience by seeing some copies of me emerge from the revolving door and do something. I pretend not to notice them, and after five minutes I go round the revolving door myself and mimic what I earlier saw the first .copy doing. Five minutes later I go round again and mimic the second copy, and so on. Meanwhile, I notice that one of the copies always repeats what I had been doing during the first five minutes. At the end of the time-travelling sequence, the virtual-reality generator will again have several records of what happened during the five minutes after noon, but this time all those records will be identical. In other words, only one history happened, namely that I met my future self but pretended not to notice. Later I became that future self, travelled back in time to meet my past self, and was apparently not noticed. That is all very tidy and non-paradoxical - and unrealistic. It was achieved by the virtual-reality generator and me engaging in an intricate, mutually referential game: I was mimicking it while it was mimicking me. But with normal interactions switched on, I can choose not to play that game.

If I really had access to virtual-reality time travel, I should cer¬tainly want to test the authenticity of the rendering. In the case we are discussing, the testing would begin as soon as I saw the copies of me. Far from ignoring them, I would immediately engage them in conversation. I am far better equipped to test their authenticity than Dr Johnson would be to test Julius Caesar's. To pass even this initial test, the rendered versions of me would effectively have to be artificial intelligent beings - moreover, beings so similar to me, at least in their responses to external stimuli, that they can convince me they are accurate renderings of how I might be five minutes from now. The virtual-reality generator must be running programs similar in content and complexity to my mind. Once again, the difficulty of writing such programs is not the issue here: we are investigating the principle of virtual-reality time travel, not its practicality. It does not matter where our hypothetical virtual-¬reality generator gets its programs, for we are asking whether the set of all possible programs does or does not include one that accurately renders time travel. But our virtual-reality generator does in principle have the means of discovering all the possible ways I might behave in various situations. This information is located in the physical state of my brain, and sufficiently precise measurements could in principle read it out. One (probably unacceptable) method of doing this would be for the virtual-reality generator to cause my brain to interact, in virtual reality, with a test environment, record its behaviour and then restore its original state, perhaps by running it backwards. The reason why this is probably unaccept¬able is that I would presumably experience that test environment, and though I should not recall it afterwards, I want the virtual-¬reality generator to give me the experiences I specify and no others.

In any case, what matters for present purposes is that, since my brain is a physical object, the Turing principle says that it is within the repertoire of a universal virtual-reality generator. So it is possible in principle for the copy of me to pass the test of whether he accurately resembles me. But that is not the only test I want to perform. Mainly, I want to test whether the time travel itself is being rendered authentically. To that end I want to find out not just whether this person is authentically me, but whether he is authentically from the future. In part I can test this by questioning him. He should say that he remembers being in my position five minutes ago and that he then travelled around the revolving door and met me. I should also find that he is testing my authenticity. Why would he do that? Because the most stringent and straightfor¬ward way in which I could test his resemblance to the future me would be to wait until I have passed through the time machine, and then look for two things: first, whether the copy of me whom I find there behaves as I remember myself behaving; and second, whether I behave as I remember the copy behaving.

In both these respects the rendering will certainly fail the test! At my very first and slightest attempt to behave differently from the way I remember my copy behaving, I shall succeed. And it will be almost as easy to make him behave differently from the way in which I behaved: all I have to do is ask him a question which I, in his place, had not been asked, and which has a distinctive answer. So however much they resemble me in appearance and personality, the people who emerge from the virtual-reality time machine are not authentic renderings of the person I am shortly to become. Nor should they be - after all, I have the firm intention not to behave as they do when it is my turn to use the time machine and, since the virtual-reality generator is now allowing me to interact freely with the rendered environment, there is nothing to prevent me from carrying out that intention.

Let me recap. As the experiment begins I meet a person who is recognizably me, apart from slight variations. Those variations consistently point to his being from the future: he remembers the laboratory at five minutes past noon, a time which, from my perspective, has not happened yet. He remembers setting out at that time, passing through the revolving door and arriving at noon. He remembers, before all that, beginning this experiment at noon and seeing the revolving door for the first time, and seeing copies of himself emerging. He says that this happened over five minutes ago, according to his subjective perception, though according to mine the whole experiment has not yet lasted five minutes. And so on. Yet though he passes all tests for being a version of me from the future, it is demonstrably not my future. When I test whether he is the specific person I am going to become, he fails that test. Similarly, he tells me that I fail the test for being his past self, since I am not doing exactly what he remembers himself doing.

So when I travel to the laboratory's past, I find that it is not the same past as I have just come from. Because of his interaction with me, the copy of me whom I find there does not behave quite as I remember behaving. Therefore, if the virtual-reality generator were to record the totality of what happens during this time-travel sequence, it would again have to store several snapshots for each instant as defined by the laboratory clock, and this time they would all be different. In other words, there would be several distinct parallel histories of the laboratory during the five-minute time~ travelling period. Again, I have experienced each of these histories in turn. But this time I have experienced them all interactively, so there is no excuse for saying that any of them are less real than the others. So what is being rendered here is a little multiverse. If this were physical time travel, the multiple snapshots at each instant would be parallel universes. Given the quantum concept of time, we should not be surprised at this. We know that the snapshots which stack themselves approximately into a single time sequence in our everyday experience are in fact parallel universes. We do not normally experience the other parallel universes that exist at the same time, but we have reason to believe that they are there. So, if we find some method, as yet unspecified, of travelling to an earlier time, why should we expect that method necessarily to take each copy of us to the particular snapshot which that copy had already experienced? Why should we expect every visitor we receive from the future to hail from the particular future snapshots in which we shall eventually find ourselves? We really should not expect this. Asking to be allowed to interact with the past environ¬ment means asking to change it, which means by definition asking to be in a different snapshot of it from the one we remember. A time traveller would return to the same snapshot (or, what is perhaps the same thing, to an identical snapshot) only in the extremely con¬trived case I discussed above, where no effective interaction takes place between the copies who meet, and the time traveller manages to make all the parallel histories identical.

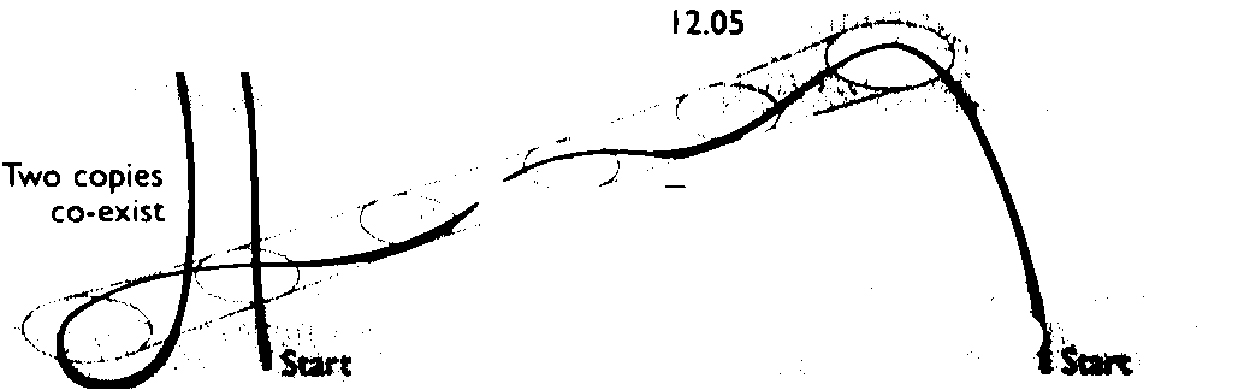

Now let me subject the virtual-reality time machine to the ultimate test. Let me deliberately set out to enact a paradox. I form the firm intention that I stated above: I resolve that if a copy of me emerges at noon from the time machine, then I shall not enter it at five minutes past noon, or indeed at any time during the experiment. But if no one emerges, then at five minutes past noon I shall enter the time machine, emerge at noon, and then not use the time machine again. What happens? Will someone emerge from the time machine or not? Yes. And no! It depends which universe we are talking about. Remember that more than one thing happens in that laboratory at noon. Suppose that I see no one emerging from the time machine, as illustrated at the point marked 'Start' at the right of Figure 12.3. Then, acting on my firm intention, I wait until five minutes past noon and then walk round that now-familiar revolving door. Emerging at noon, I find, of course, another version of myself, standing at the point marked 'Start' on the left of Figure 12.3. As we converse, we find that he and I had formed the same intention. Therefore, because I have emerged into his universe, he will behave differently from the way I behaved. Acting on the same intention as mine leads him not to use the time machine. From then on, he and I can continue to interact for as long as the simulation lasts, and there will be two versions of me in that universe. In the universe I came from, the laboratory remains empty after five minutes past twelve, for I never return to it. We have encoun¬tered no paradox. Both versions of me have succeeded in enacting our shared intention - which was therefore not, after all, logically incapable of being carried out.

Parallel universes Parallel universes

Figure 12.3 Multiverse paths of a time traveller trying to 'enact a paradox'.

I and my alter ego in this experiment have had different experiences. He saw someone emerging from the time machine at noon, and I did not. Our experiences would have been equally faithful to our intention, and equally non-paradoxical, had our roles been reversed. That is, I could have seen him emerging from the time machine at noon, and then not used it myself. In that case both of us would have ended up in the universe I started in. In the universe he started in, the laboratory would remain empty.

Which of these two self-consistent possibilities will the virtual- reality generator show me? During this rendering of an intrinsically multiversal process, I play only one of the two copies of me; the program renders the other copy. At the beginning of the experiment the two copies look identical (though in physical reality they are different because only one of them is connected to a physical brain and body outside the virtual environment). But in the physical version of the experiment - if a time machine existed physically the two universes containing the copies of me who were going to meet would initially be strictly identical, and both copies would be equally real. At the multi verse-moment when we met (in one universe) or did not meet (in the other), those two copies would become different. It is not meaningful to ask which copy of me would have which experience: so long as we are identical, there is no such thing as 'which' of us. Parallel universes do not have hidden serial numbers: they are distinguished only by what happens in them. Therefore in rendering all this for the benefit of one copy of me, the virtual-reality generator must recreate for me the effect of existing as two identical copies who then become different and have different experiences. It can cause that literally to happen by choosing at random, with equal probabilities, which of the two roles it will play (and therefore, given my intention, which role I shall play). For choosing randomly means in effect tossing some electronic version of a fair coin, and a fair coin is one that shows 'heads' in half the universes in which it is tossed and 'tails' in the other half. So in half the universes I shall play one role, and in the other half, the other. That is exactly what would happen with a real time machine.

We have seen that a virtual-reality generator's ability to render time travel accurately depends on its having detailed information about the user's state of mind. This may make one briefly wonder whether the paradoxes have been genuinely avoided. If the virtual-reality generator knows what I am going to do in advance, am I really free to perform whatever tests I choose? We need not get into any deep questions about the nature of free will here. I am indeed free to do whatever I like in this experiment, in the sense that for every possible way I may choose to react to the simulated past - including randomly, if I want to - the virtual-reality generator allows me to react in that way. And all the environments I interact with are affected by what I do, and react back on me in precisely the way they would if time travel were not taking place.

The reason why the virtual-reality generator needs information from my brain is not to predict my actions, but to render the behaviour of my counterparts from other universes. Its problem is that in the real version of this situation there would be parallel¬universe counterparts of me, initially identical and therefore possessing the same propensities as me and making the same decisions. (Farther away in the multiverse there would also be others who were already different from me at the outset of the experiment, but a time machine would never cause me to meet those versions.) If there were some other way of rendering these people, the virtual¬reality generator would not need any information from my brain, nor would it need the prodigious computational resources that we have been envisaging. For example, if some people who know me well were able to mimic me to some degree of accuracy (apart from external attributes such as appearance and tone of voice, which are relatively trivial to render) then the virtual-reality generator could use those people to act out the roles of my parallel-universe counterparts, and could thereby render time travel to that same degree of accuracy.

A real time machine, of course, would not face these problems. It would simply provide pathways along which I and my counter¬parts, who already existed, could meet, and it would constrain neither our behaviour nor our interactions when we did meet. The ways in which the pathways interconnect - that is, which snapshots the time machine would lead to - would be affected by my physical state, including my state of mind. That is no' different from the usual situation, in which my physical state, as reflected in my propensity to behave in various ways, affects what happens. The great difference between this and everyday experience is that each copy of me is potentially having a large effect on other universes (by travelling to them).

Does being able to travel to the past of other universes, but not our own, really amount to time travel? Is it just inter-universe travel that makes sense, rather than time travel? No. The processes I have been describing really are time travel. First of all, it is not the case that we cannot travel to a snapshot where we have already been. If we arrange things correctly, we can. Of course if we change anything in the past - if we make it different from how it was in the past we came from - then we find ourselves in a different past. Fully fledged time travel would allow us to change the past. In other words, it allows us to make the past different from the way we remember it (in this universe). That means different from the way it actually is, in the snapshots in which we did not arrive to change anything. And those include, by definition, the snapshots we remember being in.

So wanting to change the specific past snapshots in which we once were does indeed not make sense. But that has nothing to do with time travel. It is a nonsense that stems directly from the nonsensical classical theory of the flow of time. Changing the past means choosing which past snapshot to be in, not changing any specific past snapshot into another one. In this respect, changing the past is no different from changing the future, which we do all the time. Whenever we make a choice, we change the future: we change it from what it would have been had we chosen differently. Such an idea would make no sense in classical, spacetime physics with its single future determined by the present. But it does make sense in quantum physics. When we make a choice, we change the future from what it will be in universes in which we choose differ¬ently. But in no case does any particular snapshot in the future change. It cannot change, for there is no flow of time with respect to which it could change. 'Changing' the future means choosing which snapshot we will be in; 'changing' the past means exactly the same thing. Because there is no flow of time, there is no such thing as changing a particular past snapshot, such as one we remem¬ber being in. Nevertheless, if we somehow gain physical access to the past, there is no reason why we could not change it in precisely the sense in which we change the future, namely by choosing to be in a different snapshot from the one we would have been in if we had chosen differently.

Arguments from virtual reality help in understanding time travel because the concept of virtual reality requires one to take 'counter¬factual events' seriously, and therefore the multi-universe quantum concept of time seems natural when it is rendered in virtual reality. By seeing that past-directed time trav~1 is within the repertoire of a universal virtual-reality generator, we learn that the idea of past-directed time travel makes perfect sense. But that is not to say that it is necessarily physically achievable. After all, faster-than¬light travel, perpetual motion machines and many other physical impossibilities are all possible in virtual reality. No amount of reasoning about virtual reality can prove that a given process is permitted by the laws of physics (though it can prove that it is not: if we had reached the contrary conclusion, it would have implied, via the Turing principle, that time travel cannot occur physically). So what do our-positive conclusions about virtual-reality time travel tell us about physics?

They tell us what time travel would look like if it did occur. They tell us that past-directed time travel would inevitably be a process set in several interacting and interconnected universes. In that process, the participants would in general travel from one universe to another whenever they travelled in time. The precise ways in which the universes were connected would depend, among other things, on the participants' states of mind.

So, for time travel to be physically possible it is necessary for there to be a multiverse. And it is necessary that the physical laws governing the multiverse be such that, in the presence of a time machine and potential time travellers, the uni'{erses become inter¬connected in the way I have described, and not in any other way. For example, if I am not going to use a time machine come what may, then no time-travelling versions of me must appear in my snapshot; that is, no universes in which versions of me do use a time machine can become connected to my universe. If I am defi¬nitely going to use the time machine, then my universe must become connected to another universe in which I also definitely use it. And if I am going to try to enact a 'paradox' then, as we have seen, my universe must become connected with another one in which a copy of me has the same intention as I do, but by carrying out that intention ends up behaving differently from me. Remarkably, all this is precisely what quantum theory does predict. In short, the result is that if pathways into the past do exist, travellers on them are free to interact with their environment in just the same way as they could if the pathways did not lead into the past. In no case does time travel become inconsistent, or impose special constraints on time travellers' behaviour.

That leaves us with the question whether it is physically possible for pathways into the past to exist. This question has been the subject of much research, and is still highly controversial. The usual starting-point is a set of equations which form the (predictive) basis of Einstein's general theory of relativity, currently our best theory of space and time. These equations, known as Einstein's equations, have many solutions, each describing a possible four-dimensional configuration of space, time and gravity. Einstein's equations cer¬tainly permit the existence of pathways into the past; many solu¬tions with that property have been discovered. Until recently, the accepted practice has been systematically to ignore such solutions. But this has not been for any reason arising from within the theory, nor from any argument within physics at all. It has been because physicists were under the impression that time travel would 'lead to paradoxes', and that such solutions of Einstein's equations must therefore be 'unphysical'. This arbitrary second-guessing is remi¬niscent of what happened in the early years of general relativity, when the solutions describing the Big Bang and an expanding uni¬verse were rejected by Einstein himself. He tried to change the equations so that they would describe a static universe instead. Later he referred to this as the biggest mistake of his life, and the expansion was verified experimentally by the American astronomer Edwin Hubble. For many years also, the solutions obtained by the German astronomer Karl Schwarzschild, which were the first to describe black holes, were mistakenly rejected as 'unphysical'. They described counter-intuitive phenomena, such as a region from which it is in principle impossible to escape, and gravitational forces becoming infinite at the black hole's centre. The prevailing view nowadays is that black holes do exist, and do have the properties predicted by Einstein's equations.

Taken literally, Einstein's equations predict that travel into the past would be possible in the vicinity of massive, spinning objects, such as black holes, if they spun fast enough, and in certain other situations. But many physicists doubt that these predictions are realistic. No sufficiently rapidly spinning black holes are known, and it has been argued (inconclusively) that it may be impossible to spin one up artificially, because any rapidly spinning material that one fired in might be thrown off and be unable to enter the black hole. The sceptics may be right, but in so far as their reluc¬tance to accept the possibility of time travel is rboted in a belief that it leads to paradoxes, it is unjustified.

Even when Einstein's equations have been more fully understood, they will not provide conclusive answers on the subject of time travel. The general theory of relativity predates quantum theory and is not wholly compatible with it. No one has yet succeeded in formulating a satisfactory quantum version - a quantum theory of gravity. Yet, from the arguments I• have given, quantum effects would be dominant in time-travelling situations. Typical candidate versions of a quantum theory of gravity not only allow past-directed connections to exist in the multiverse, they predict that such connec¬tions are continually forming and breaking spontaneously. This is happening throughout space and time, but only on a sub¬microscopic scale. The typical pathway formed by these effects is about 10-35 metres across, remains open for one Planck time (about 10-43 seconds), and therefore reaches only aboijt one Planck time into the past.

Future-directed time travel, which essentially requires only efficient rockets, is on the moderately distant but confidently fore¬seeable technological horizon. Past-directed time travel, which requires the manipulation of black holes, or some similarly violent gravitational disruption of the fabric of space and time, will be practicable only in the remote future, if at all. At present we know of nothing in the laws of physics that rules out past-directed time travel; on the contrary, they make it plausible that time travel is possible. Future discoveries in fundamental physics may change this. It may be discovered that quantum fluctuations in space and time become overwhelmingly strong near time machines, and effec¬tively seal off their entrances (Stephen Hawking, for one, has argued that some calculations of his make this likely, but his argument is inconclusive). Or some hitherto unknown phenomenon may rule out past-directed time travel- or provide a new and easier method of achieving it. One cannot predict the future growth of knowledge. But if the future development of fundamental physics continues to allow time travel in principle, then its practical attainment will surely become a mere technological problem that will eventually be solved.

Because no time machine provides pathways to times earlier than the moment at which it came into existence, and because of the way in which quantum theory says that universes are intercon¬nected, there are some limits to what we can expect to learn by using time machines. Once we have built one, but not before, we may expect visitors, or at least messages, from the future to emerge from it. What will they tell us? One thing they will certainly not tell us is news of our own future. The deterministic nightmare of the prophecy of an inescapable future doom, brought about in spite of - or perhaps as the very consequence of - our attempts to avoid it, is the stuff of myth and science fiction only. Visitors from the future cannot know our future any more than we can, for they did not come from there. But they can tell us about the future of their universe, whose past was identical to ours. They can bring taped news and current affairs programmes, and newspapers with dates starting from tomorrow and onwards. If their society made some mistaken decision, which led to disaster, they can warn us of it. We mayor may not follow their advice. If we follow it, we may avoid the disaster, or - there can be no guarantees - we may find that the result is even worse than what happened to them.

On average, though, we should presumably benefit greatly from studying their future history. Although it is not our future history, and although knowing of a possible impending disaster is not the same thing as knowing what to do about it, we should presumably learn much from such a detailed record of what, from our point of view, might happen.

Our visitors might bring details of great scientific and artistic achievements. If these were made in the near future of the other universe, it is likely that counterparts of the people who made them would exist in our universe, and might already be working towards those achievements. All at once, they would be presented with completed versions of their work. Would they be grateful? There is another apparent time-travel paradox here. Since it does not appear to create inconsistencies, but merely curiosities, it has been discussed more in fiction than in scientific arguments against time travel (though some philosophers, such as Michael Dummett, have taken it seriously). I call it the knowledge paradox of time travel; here is how the story typically goes. A future historian with an interest in Shakespeare uses a time machine to visit the great play¬wright at a time when he is writing Hamlet. They have a conver¬sation, in the course of which the time traveller shows Shakespeare the text of Hamlet's 'To be or not to be' soliloquy, which he has brought with him from the future. Shakespeare likes it and incorporates it into the play. In another version, Shakespeare dies and the time traveller assumes his identity, achieving success by pretending to write plays which he is secretly copying from the Complete Works of Shakespeare, which he brought with him from the future. In yet another version, the time traveller is puzzled by not being able to locate Shakespeare at all. Through some chain of accidents, he finds himself impersonating Shakespeare and, again, plagiarizing his plays. He likes the life, and years later he realizes that he has become the Shakespeare: there never had been another one.

Incidentally, the time machine in these stories would have to be provided by some extraterrestrial civilization which had already achieved time travel by Shakespeare's day, and which was willing to allow our historian to use one of their scarce, non-renewable slots for travelling back to time. Or perhaps (even less likely, I guess) there might be a usable, naturally occurring time machine in the vicinity of some black hole.

All these stories relate a perfectly consistent chain - or rather, circle - of events. The reason why they are puzzling, and deserve to be called paradoxes, lies elsewhere. It is that in each story great literature comes into existence without anyone having written it: no one originally wrote it, no one has created it. And that proposition, though logically consistent, profoundly contradicts our understand¬ing of where knowledge comes from. According to the epistemo¬logical principles I set out in Chapter 3, knowledge does not come into existence fully formed. It exists only as the result of creative processes, which are step-by-step, evolutionary processes, always starting with a problem and proceeding with tentative new theories, criticism and the elimination of errors to a new and preferable problem-situation. This is how Shakespeare wrote his plays. It is how Einstein discovered his field equations. It is how all of us succeed in solving any problem, large or small, in our lives, or in creating anything of value.

It is also how new living species come into existence. The ana¬logue of a 'problem' in this case is an ecological niche. The 'theories' are genes, and the tentative new theories are mutated genes. The 'criticism' and 'elimination of errors' are natural selection. Knowledge is created by intentional human action, biological adaptations by a blind, mindless mechanism. The words we use to describe the two processes are different, and the processes are physically dissimilar too, but the detailed laws of epistemology that govern them both are the same. In one case they are called Popper's theory of the growth of scientific knowledge; in the other, Darwin's theory of evolution. One could formulate a knowledge paradox just as well in terms of living species. Say we take some mammals in a time machine to the age of the dinosaurs, when no mammals had yet evolved. We release our mammals. The dinosaurs die out and our mammals take over. Thus new species have come into existence without having evolved. It is even easier to see why this version is philosophically unacceptable: it implies a non-Darwinian origin of species, and specifically creationism. Admittedly, no Creator in the traditional sense is invoked. Nevertheless the origin of species in this story is distinctly supernatural; the story gives no explanantion - and rules out the possibility of there being an explanation- of how the specific and complex adaptations of species to their niches got there.

In this way, knowledge-paradox situations violate epistemological or, if you like, evolutionary principles. They are paradoxical only because they involve the creation, out of nothing, of complex human knowledge or of complex biological adaptations. Analogous stories with other sorts of object or information on the loop are not paradoxical. Observe a pebble on a beach; then travel back to yesterday, locate the pebble elsewhere and move it to where you• are going to find it. Why did you find it at that particular location? Because you moved it there. Why did you move it there? Because you found it there. You have caused some information (the position of the pebble) to come into existence on a self-consistent loop. But so what? The pebble had to be somewhere. Provided the story does not involve getting something for nothing, by way of knowledge or adaptation, it is no paradox.

In the multiverse view, the time traveller who visits Shakespeare has not come from the future of that copy of Shakespeare. He can affect, or perhaps replace, the copy he visits. But he can never visit the copy who existed in the universe he started from. And it is that copy who wrote the plays. So the plays had a genuine author, and there are no paradoxical loops of the kind envisaged in the story. Knowledge and adaptation are, even in the presence of pathways to the past, brought into existence only incrementally, by acts of human creativity or biological evolution, and in no other way.

I wish I could report that this requirement, is also rigorously implemented by the laws that quantum theory imposes on the multiverse. I expect it is, but this is hard to prove because it is hard to express the desired property in the current language of theoretical physics. What mathematical formula distinguishes 'knowledge' or 'adaptation' from worthless information? What physical attributes distinguish a 'creative' process from a non-¬creative one? Although we cannot yet answer these questions, I do not think that the situation is hopeless. Remember the conclusions of Chapter 8, about the significance of life and of knowledge in the multiverse. I pointed out there (for reasons quite unconnected with time travel) that knowledge creation and biological evolution are physically significant processes. And one of the reasons was that those processes, and only those, have a particular effect on parallel universes - namely to create trans-universe structure by making them become alike. When, one day we understand the details of this effect, we may be able to define knowledge adaptation, creativity and evolution in terms of the convergence of universes.

When I 'enact a paradox', there are eventually two copies of me in one universe and none in the other. It is a general rule that after time travel has taken place the total number of copies of me counted across all universes, is unchanged. Similarly the usual conservation laws for mass, energy and other physical quantities continue to hold for the multiverse as a whole, though not necessarily in any one universe. However, there is no conservation law for knowledge. Possession of a time machine would allow us access to knowledge from an entirely new source, namely the creativity of minds in other universes. They could also receive knowledge from us, so one can loosely speak of a 'trade' in knowledge - and indeed a trade in artefacts embodying knowledge - across many universes. But one cannot take that analogy too literally. The multi¬verse will never be a free-trade area because the laws of quantum mechanics impose drastic restrictions on which snapshots can be connected to which others. For one thing, two universes first become connected only at a moment when they are identical: becoming connected makes them begin to diverge. It is only when those differences have accumulated, and new knowledge has been created in one universe and sent back in time to the other

|

|

|

|

|

Fox

Magister

Gender:

Posts: 122

Reputation: 6.10

Rate Fox

Never underestimate the odds.

|

|

Re:Anyone up for a little Time Travel?

« Reply #4 on: 2007-07-07 17:19:05 » |

|

Wow, some excellent and interesting responces here.

Speaking hypothetically, and looking at the topic from a logical point of view (using both Occam's razor and the "space-time travel" concept) I would personally say that "time travel", within a single universe, back or forwards along it's own time-line, would be completely impossible given the paradoxes of such events alone. Of course we are, in a sense, all "time travelers" every waking moment of our lives but I'm more refering to a method via some sort of machine or through the manipulation of physics in some way.

While I disagree that "time travel" would be possible along the time-line of a single universe I don't (again, hypothetically speaking) necessarily disagree with the concept itself. I think it would be more logical to speculate that such a method would result in actual "space-time travel". What I mean by that is, you would travel beyond the known universe (backwards or forwards) into the space-time of a parallel universe most likely very similar to our own. The paradoxes in this example simply don't apply, and thus never occur. You would be in the history of a completely different (although possibly very similar) universe altogeather.

As for myself, I would, given the chance, like to travel back to the formation of both the planet and life on Earth and thoroughly document them, there processes and there stages of evolutionary development. I would then travel back to the future, with all my hard evidences and data and finally put an end to religious babble and claim the nobel prize

Whilst travelling through the past I would also spread the CoV meme to some of the greatest minds and nations the world has known, who would hopefully become infected with the logic of the idea and propergate it even further throughout history. It wold also provide a wonderful opportunity to factually repudiate the existence of Christ and so much other religious nonsense.

Oh the joy!

|

I've never expected a miracle. I will get things done myself. - Gatsu

|

|

|

|