Author

Author

|

Topic: Dennett on chess and artificial intelligence (Read 5391 times) |

|

Blunderov

Archon

Gender:

Posts: 3160

Reputation: 8.30

Rate Blunderov

"We think in generalities, we live in details"

|

|

Dennett on chess and artificial intelligence

« on: 2007-08-28 13:31:08 » |

|

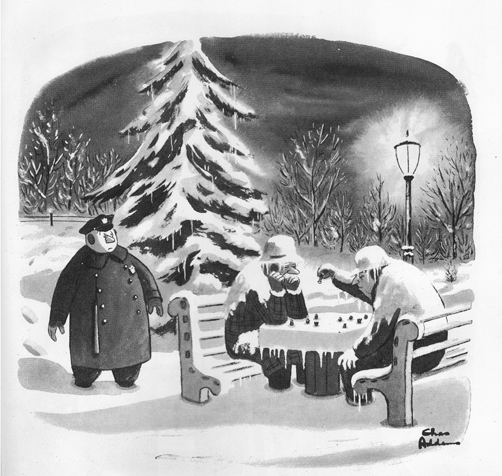

[Blunderov] The inimitable Charles Addams

Source: mindhacks.com

Dennett on chess and artificial intelligence

http://www.technologyreview.com/Infotech/19179/

Higher Games

It's been 10 years since IBM's Deep Blue beat Garry Kasparov in chess. A prominent philosopher asks what the match meant.

By Daniel C. Dennett

In the popular imagination, chess isn't like a spelling bee or Trivial Pursuit, a competition to see who can hold the most facts in memory and consult them quickly. In chess, as in the arts and sciences, there is plenty of room for beauty, subtlety, and deep originality. Chess requires brilliant thinking, supposedly the one feat that would be--forever--beyond the reach of any computer. But for a decade, human beings have had to live with the fact that one of our species' most celebrated intellectual summits--the title of world chess champion--has to be shared with a machine, Deep Blue, which beat Garry Kasparov in a highly publicized match in 1997. How could this be? What lessons could be gleaned from this shocking upset? Did we learn that machines could actually think as well as the smartest of us, or had chess been exposed as not such a deep game after all?

The following years saw two other human-machine chess matches that stand out: a hard-fought draw between Vladimir Kramnik and Deep Fritz in Bahrain in 2002 and a draw between Kasparov and Deep Junior in New York in 2003, in a series of games that the New York City Sports Commission called "the first World Chess Championship sanctioned by both the Fédération Internationale des Échecs (FIDE), the international governing body of chess, and the International Computer Game Association (ICGA)."

The verdict that computers are the equal of human beings in chess could hardly be more official, which makes the caviling all the more pathetic. The excuses sometimes take this form: "Yes, but machines don't play chess the way human beings play chess!" Or sometimes this: "What the machines do isn't really playing chess at all." Well, then, what would be really playing chess?

This is not a trivial question. The best computer chess is well nigh indistinguishable from the best human chess, except for one thing: computers don't know when to accept a draw. Computers--at least currently existing computers--can't be bored or embarrassed, or anxious about losing the respect of the other players, and these are aspects of life that human competitors always have to contend with, and sometimes even exploit, in their games. Offering or accepting a draw, or resigning, is the one decision that opens the hermetically sealed world of chess to the real world, in which life is short and there are things more important than chess to think about. This boundary crossing can be simulated with an arbitrary rule, or by allowing the computer's handlers to step in. Human players often try to intimidate or embarrass their human opponents, but this is like the covert pushing and shoving that goes on in soccer matches. The imperviousness of computers to this sort of gamesmanship means that if you beat them at all, you have to beat them fair and square--and isn't that just what Kasparov and Kramnik were unable to do?

Yes, but so what? Silicon machines can now play chess better than any protein machines can. Big deal. This calm and reasonable reaction, however, is hard for most people to sustain. They don't like the idea that their brains are protein machines. When Deep Blue beat Kasparov in 1997, many commentators were tempted to insist that its brute-force search methods were entirely unlike the exploratory processes that Kasparov used when he conjured up his chess moves. But that is simply not so. Kasparov's brain is made of organic materials and has an architecture notably unlike that of Deep Blue, but it is still, so far as we know, a massively parallel search engine that has an outstanding array of heuristic pruning techniques that keep it from wasting time on unlikely branches.

http://www.technologyreview.com/Infotech/19179/page2/

True, there's no doubt that investment in research and development has a different profile in the two cases; Kasparov has methods of extracting good design principles from past games, so that he can recognize, and decide to ignore, huge portions of the branching tree of possible game continuations that Deep Blue had to canvass seriatim. Kasparov's reliance on this "insight" meant that the shape of his search trees--all the nodes explicitly evaluated--no doubt differed dramatically from the shape of Deep Blue's, but this did not constitute an entirely different means of choosing a move. Whenever Deep Blue's exhaustive searches closed off a type of avenue that it had some means of recognizing, it could reuse that research whenever appropriate, just like Kasparov. Much of this analytical work had been done for Deep Blue by its designers, but Kasparov had likewise benefited from hundreds of thousands of person-years of chess exploration transmitted to him by players, coaches, and books.

It is interesting in this regard to contemplate the suggestion made by Bobby Fischer, who has proposed to restore the game of chess to its intended rational purity by requiring that the major pieces be randomly placed in the back row at the start of each game (randomly, but in mirror image for black and white, with a white-square bishop and a black-square bishop, and the king between the rooks). Fischer Random Chess would render the mountain of memorized openings almost entirely obsolete, for humans and machines alike, since they would come into play much less than 1 percent of the time. The chess player would be thrown back onto fundamental principles; one would have to do more of the hard design work in real time. It is far from clear whether this change in rules would benefit human beings or computers more. It depends on which type of chess player is relying most heavily on what is, in effect, rote memory.

The fact is that the search space for chess is too big for even Deep Blue to explore exhaustively in real time, so like Kasparov, it prunes its search trees by taking calculated risks, and like Kasparov, it often gets these risks precalculated. Both the man and the computer presumably do massive amounts of "brute force" computation on their very different architectures. After all, what do neurons know about chess? Any work they do must use brute force of one sort or another.

It may seem that I am begging the question by describing the work done by Kasparov's brain in this way, but the work has to be done somehow, and no way of getting it done other than this computational approach has ever been articulated. It won't do to say that Kasparov uses "insight" or "intuition," since that just means that Kasparov himself has no understanding of how the good results come to him. So since nobody knows how Kasparov's brain does it--least of all Kasparov himself--there is not yet any evidence at all that Kasparov's means are so very unlike the means exploited by Deep Blue.

http://www.technologyreview.com/Infotech/19179/page3/

People should remember this when they are tempted to insist that "of course" Kasparov plays chess in a way entirely different from how a computer plays the game. What on earth could provoke someone to go out on a limb like that? Wishful thinking? Fear?

In an editorial written at the time of the Deep Blue match, "Mind over Matter" (May 10, 1997), the New York Times opined:

The real significance of this over-hyped chess match is that it is forcing us to ponder just what, if anything, is uniquely human. We prefer to believe that something sets us apart from the machines we devise. Perhaps it is found in such concepts as creativity, intuition, consciousness, esthetic or moral judgment, courage or even the ability to be intimidated by Deep Blue.

The ability to be intimidated? Is that really one of our prized qualities? Yes, according to the Times:

Nobody knows enough about such characteristics to know if they are truly beyond machines in the very long run, but it is nice to think that they are.

Why is it nice to think this? Why isn't it just as nice--or nicer--to think that we human beings might succeed in designing and building brainchildren that are even more wonderful than our biologically begotten children? The match between Kasparov and Deep Blue didn't settle any great metaphysical issue, but it certainly exposed the weakness in some widespread opinions. Many people still cling, white-knuckled, to a brittle vision of our minds as mysterious immaterial souls, or--just as romantic--as the products of brains composed of wonder tissue engaged in irreducible noncomputational (perhaps alchemical?) processes. They often seem to think that if our brains were in fact just protein machines, we couldn't be responsible, lovable, valuable persons.

Finding that conclusion attractive doesn't show a deep understanding of responsibility, love, and value; it shows a shallow appreciation of the powers of machines with trillions of moving parts.

Daniel Dennett is the codirector of the Center for Cognitive Studies at Tufts University, where he is also a professor of philosophy.

|

|

|

|

|

Walter Watts

Archon

Gender:

Posts: 1571

Reputation: 8.25

Rate Walter Watts

Just when I thought I was out-they pull me back in

|

|

Re:Dennett on chess and artificial intelligence

« Reply #1 on: 2007-08-28 16:15:16 » |

|

Quote from: Blunderov on 2007-08-28 13:31:08 <snip>

People should remember this when they are tempted to insist that "of course" Kasparov plays chess in a way entirely different from how a computer plays the game. What on earth could provoke someone to go out on a limb like that? Wishful thinking? Fear?

<snip>

|

I'll bet you everyone out on that particular limb is a theist!

Walter

|

Walter Watts

Tulsa Network Solutions, Inc.

No one gets to see the Wizard! Not nobody! Not no how!

|

|

|

the.bricoleur

Adept

Posts: 341

Reputation: 7.77

Rate the.bricoleur

making sense of change

|

|

Re:Dennett on chess and artificial intelligence

« Reply #2 on: 2007-09-14 10:12:30 » |

|

Quote from: Blunderov on 2007-08-28 13:31:08

[Blunderov]

It is interesting in this regard to contemplate the suggestion made by Bobby Fischer, who has proposed to restore the game of chess to its intended rational purity by requiring that the major pieces be randomly placed in the back row at the start of each game (randomly, but in mirror image for black and white, with a white-square bishop and a black-square bishop, and the king between the rooks). Fischer Random Chess would render the mountain of memorized openings almost entirely obsolete, for humans and machines alike, since they would come into play much less than 1 percent of the time. The chess player would be thrown back onto fundamental principles; one would have to do more of the hard design work in real time. It is far from clear whether this change in rules would benefit human beings or computers more. It depends on which type of chess player is relying most heavily on what is, in effect, rote memory. |

"Interesting" is an understatement !!!

Blunderov, to your knowledge are people at least trying 'Fischer Random Chess' ??

-iolo

|

|

|

|

|

Blunderov

Archon

Gender:

Posts: 3160

Reputation: 8.30

Rate Blunderov

"We think in generalities, we live in details"

|

|

Re:Dennett on chess and artificial intelligence

« Reply #3 on: 2007-09-14 12:28:49 » |

|

Quote from: Iolo Morganwg on 2007-09-14 10:12:30

Blunderov, to your knowledge are people at least trying 'Fischer Random Chess' ??

|

[Blunderov] Yes indeed they are. The variant is available on the Internet Chess Club. I imagine it is widely available elsewhere too. I was once invited to "give up my obsession with classical chess" and come over to Fischer Random (the dark side?) but my habits are too well set.

Perhaps the most significant contribution that Fisher has made to the way chess is played are the so called "Fischer clocks." These are not really special clocks but a method wherebye each player has an amount of time added to his or her clock after each move. This has lead also to the demise of the adjournment, somewhat to my regret. There was a special drama in pulling an all-nighter over a tricky endgame and then turning up to finish the game in a nearly empty tournament hall the next morning desperately short of sleep but full of secret plans and clever tricks. The game is the poorer in my view but "watcha gonna do?" as they say.

I include this wonderful photograph of Alexandra Kosteniuk* who demonstrates the art of power dressing for simultaneous exhibitions. (Red works well too. Teams that have red uniforms do better than teams without. Strange but true.)

Kosteniuk is very proficient at Fischer random chess as well as classical chess.

* http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexandra Kosteniuk

Alexandra Kosteniuk (born April 23, 1984 in Perm, Volga Federal District) is a Russian chess player who became female European champion in 2004 by winning the tournament in Dresden, Germany. In August 2006 she became the first Chess960 (Fischer Random) women world champion after beating Germany's top female player Elisabeth Pähtz 5.5-2.5.

In November 2004, she achieved the International Grandmaster title, becoming the tenth of the eleven women who have received the highest title awarded by the World Chess Federation (FIDE). She also holds the titles of Woman Grandmaster and International Master. She is third on the October 2006 FIDE women Elo rating list with a rating of 2534. Kosteniuk won the 2005 Russian Women's Championship, held from May 14 to 26 in Samara, Russia, finishing with a score of +7 =4 -0.

Kosteniuk's mottos have been "chess is cool" and "beauty and intelligence can go together". With these as a backdrop, Kosteniuk has been promoting chess in the capacity of a fashion model in order to spark interest in the game around the world. She is also the host of a popular podcast "Chess is Cool".

On April 22, 2007 she gave birth to a daughter, Francesca Maria.

Her website (see below) covers the events she is playing in and contains a large photo gallery.

|

|

|

|

|

|